I have no recollection of walking into the Mayday Hospital in Croydon on my first day of work as a qualified doctor. I do not think that it felt especially momentous. In fact, after such a long journey to that exact moment, I am sure it felt anticlimactic. In 1980, there was no organised induction or introduction to the hospital for brand-new doctors. Instead, slightly less junior doctors passed on their wisdom in short briefings, performed as an act of comradeship, or philanthropically in the interests of public safety. One of the outgoing house officers gave me a dire warning. The sisters on my ward, he told me, were lovely, but the sister on the ward where he worked was a harridan, a total nightmare to be avoided at all costs. As I would sometimes have patients on her ward, I needed to know this. He implied that it was best to go off sick if one of my patients was admitted there.

My first day was uneventful. Patients were respectful. Nurses with years of experience gave me blood results to interpret. It was pretty obvious that I would be of little use to anyone if I constantly let my self-doubt show, but it was equally obvious that I needed to be realistic about my own expertise. So I blagged my way through that first day, and, to be truthful, I have felt that I have been blagging my way through ever since. I have come to feel that so-called imposter syndrome is just an expression of normal levels of self-awareness. It is the doctors who do not feel like imposters that you need to worry about.

The other two junior doctors in the team were both women. Nicki and Marie were older than me by a year or so. Nicki was an able and intelligent registrar who went on to become a GP. Marie, the SHO, was altogether fierier, a small, fast moving woman who went on to be a consultant in emergency medicine. The three of us got on well, which was lucky, because we were forced to spend a lot of time together. Without respect and trust within the whole team, a junior doctor’s life could be nightmarish.

The main instrument that was used to give junior doctors a hard time was the Bleep. Junior doctors worked under the tyranny of the Bleep and it was a resented part of my life for many years. As a house officer, I was completely at its mercy. The primitive pager was forever bleeping, imperiously demanding that I phone the hospital switchboard in order to be directed to deal with matters that ranged from trivial (mostly) to grave (occasionally). The demands of the Bleep created an inner tension, as they frustrated my efforts to get through my To Do List. As the most junior member of the team, it was my job to mop up a wide range of repetitive tasks that were banal, but important to the welfare of patients. For example, it fell to me to re-write patients’ drug charts, which was boring, but if I should make an error, the consequences were potentially lethal. The To Do List grew each morning as we did our daily ward round. If I did not clear the list by the time I went home each day, it would lengthen exponentially, so I had little option but to stay at work until everything was done. This made long hours even longer.

When I was on-call, the Bleep would from time to time emit an explosive noise that was designed to grab attention and to cause alarm. This indicated that a cardiac arrest had occurred. A tiny and tinny voice from within the Bleep would state the location of the unfortunate patient, and then I had to run, white coat streaming behind me, slamming through doors whilst patients, staff and visitors pressed themselves to the walls to let me pass. I would arrive breathless at the bedside and had to snap into a physically and emotionally demanding routine. There was a single cardiac arrest trolley for all of the general wards, and one of us had to fetch it. It contained an electrocardiogram (ECG) machine, a cardiac defibrillator and equipment to intubate the patient. Whoever arrived first, which was usually me, had to check if the patient had a pulse in their neck, and if they did not, hit them hard on the chest with a clenched fist. Occasionally this would restart their heart immediately. Thereafter, my job was to perform cardiac massage. I was allocated this most repetitive and tiring of tasks on the questionable grounds that I was the strongest of the three of us. It did not escape my attention that the job also involved no intellectual effort. Marie would get an intravenous line into the patient, a really tricky job when the circulation has stopped. Nicki would do an ECG, decide when to defibrillate, and choose which drugs to administer. Sadly, only a small proportion of our cardiopulmonary resuscitations (CPRs) resulted in the patient leaving the hospital alive, mainly because the procedure was applied indiscriminately and often involved patients who were too ill or too old to benefit. It was troubling to revive someone so that they could spend a few uncomfortable days in the Intensive Care Unit, only to die anyway.

The Bleep could summon me in this way at any moment, day or night. Always slow to wake up, I found the instant transition from sleep to high drama difficult to negotiate. Anticipation marred the few hours I spent in bed when I was on call, with the Bleep’s red light taunting me through the darkness. Only a minority of calls concerned matters of life and death. The Bleep frequently woke me to authorise night sedation for sleepless patients. Such was my hostility to the hateful plastic brick that I dropped it down the toilet twice, thus proving that Freud’s theories about unconscious motivation had some merit.

The former Mayday Hospital is in Thornton Heath, about 7 miles south of central London. It has been renamed Croydon University Hospital since I worked there, possibly because local wags called it the May-Die Hospital. My great-aunts were upset that I was working at the Mayday, as it was, in their opinion, a bad hospital. A cousin of my mother’s, Keith, had died there forty years earlier. A middle ear infection had spread to the sinuses in his mastoid bone, causing an abscess. Mastoiditis was a common and feared childhood condition until antibiotics became available, and children commonly died as a result.

The only thing that I ever knew about Keith, other than his sad death, was that, at one of the family Sunday teatime gatherings, he ate the prawn heads and tails and left the edible parts on his plate. Consuming the inedible was something of a pattern in our family. My sister once ate a Plaster of Paris snowman from a Christmas cake. A cousin of mine once complained that the honey on his toast tasted horrible. The adults insisted that he eat it all up, until my mother noticed a rancid smell and realised that my grandmother had left bacon fat in a honey jar many months before. Surprisingly, no medical complications arose from these gastronomic lapses.

The Mayday was a large hospital, similar to the Brook in that the original late Victorian building had been extended and rebuilt in a jumble of architectural styles. The medical staff were organised into clinical firms, a system that was ubiquitous throughout the UK at the time. The medical residency system was brought to the UK from Johns Hopkins Hospital when Sir William Osler left Baltimore to become Regius Professor of Medicine in Oxford in 1905. The idea was that the medical staff in training, who were assumed to be young men with no commitments beyond their profession, lived in the hospital in order to maximise their opportunities to learn at the bedside. It was a type of intense apprenticeship. Junior doctors were organised hierarchically by grade, and the firm was headed by the non-resident consultant, who took responsibility for all the clinical decisions that the firm made. If a junior doctor made a mistake, it was the consultant’s responsibility for allowing them to do something beyond their ability. Resident medical staff were given free board and lodging, but they were not paid for out of hours work. Out-of-hours work continued to attract no remuneration until the successful junior doctors’ strike of 1975, after which a payment of 30% of the daytime hourly rate was introduced.

Our firm was led by Dr Roland Fanthorpe, a thoughtful and universally respected physician of the generation that trained during the Second World War. He was a quiet man who sported a full head of white hair. He had been appointed Consultant Chest Physician at the Mayday in 1952, with responsibility for 100 beds, most of which were occupied by people with tuberculosis. In the same year, triple drug therapy with streptomycin, para-aminosalicylic acid and isoniazid was introduced, which transformed the treatment of tuberculosis, and there was a sharp reduction in the need for inpatient beds for respiratory medicine.

The wards were in the Nightingale style with high ceilings and large windows. The beds lined the walls in two rows and the nurses worked from desks in the middle of the ward. Close to the door there was a glass sided ward office and several side rooms. On days when we were the admitting team for medicine (“on-take”), we dealt with all acute adult illnesses that did not require surgery. The bulk of our routine, non-emergency, work was related to asthma or the consequences of smoking, namely chronic obstructive airways disease and lung cancer. Some of the respiratory patients had had thoracotomies as treatment for tuberculosis many years before. This procedure was disfiguring but often lifesaving. It involved the removal of ribs from the upper part of the chest to collapse tuberculous cavities in the lung, allowing them to heal. It was not a perfect treatment, and the disease sometimes recurred.

Some of my contemporaries had lobbied hard to secure the most prestigious of the house jobs, but I did not bother, as I doubted that it would affect my appointment to a psychiatric training scheme. I let fate decide where I would work during my pre-registration year, and I soon realised that I had landed on my feet at the Mayday. The outcome for my second house job was altogether less propitious, and my six months as a house surgeon were pretty miserable. Roland Fanthorpe was a truly excellent doctor, a nice man who was gentle with the patients, supportive of his junior staff and well-liked by the nurses. I never heard him raise his voice, and if we needed to contact him for advice at night, he would offer to come in. He liked to teach and there was plenty of laughter, but there was a background air of sadness about him. He died of a heart attack a couple of years after I worked with him, and his obituary mentioned an unhappy home life. Like most of the doctors whom I admired early in my career, Roland Fanthorpe did no private practice. Unlike nearly all of my other early role models, he made no contributions to the scientific literature.

There were three general medical firms at the Mayday, each with a specialism. We worked Monday to Friday nine-to-five, and the out of hours work was divided between us. Every third night was worked in a continuous day-night-day stretch. One weekend in three was worked continuously from Friday morning to Monday evening. We worked 84 hours per week, excluding sickness and holiday cover. The hours were ridiculously excessive, but they were commonplace. In some jobs, junior doctors had to work alternate nights. If you secured one particularly sought-after surgical house job in a central London teaching hospital, you were expected to stay in the hospital continuously for six-months, leaving only for a few hours to have your hair cut. Although originally introduced to improve medical training, the pattern of work extracted 24-hour hospital cover at low cost from an inadequate number of doctors. It was abolished many years later, when the UK’s Medical Exception to the European Working Time Directive became politically embarrassing, but even today many junior doctors continue to work in excess of 48 hours per week, for a variety of reasons.

Our pace of work was brisk, and it rarely slackened until late in the evening, long after the pubs had turned out. As the medical dogsbody, I would generally get about five hours of interrupted sleep during a night on-call. No-one would have allowed a lorry driver or an airline pilot to work such hours, but the whole hospital system depended on young doctors making fateful decisions in a state of exhaustion. The effect on my personal life was severe. I routinely fell asleep on the bus on the way home. The bus conductor learned to wake me at my stop. I would eat dinner and immediately fall asleep in front of the television. In the morning, there was a constant risk of oversleeping, and at weekends I rarely rose before midday. On those days that started and finished at home, I was reasonably alert and able to converse with my wife, but if we went to the cinema, I would fall asleep as soon as the lights went down. I constantly nodded off in the pub, at gigs and in restaurants.

I think that heroic overwork fed into dysfunctional beliefs about doctors’ supposed super-human abilities, beliefs that were held by the profession and the public alike at that time. I coped because I was young and strong, and I enjoyed the work. There was an adrenalin rush at the front line of medicine and the junior doctors at the Mayday formed a tight-knit group. We were well looked after by each other and by the people around us. The hours were terrible but otherwise the working conditions were much better than they are today. There was hot food available in the evening, and we had reasonably comfortable bedrooms to retreat to. I developed bags under my eyes that have never gone away, but I learned more in that six months than I had in the entire five years at medical school. Some of the work was distressing, and some incidents still haunt me, but I became the doctor that I am now, for better or worse. A lot of what was most important was taught to me by nurses and much of that had direct application to psychiatry. As an undergraduate, I sometimes had serious doubts about medicine, but my medical house job convinced me that I had not made a mistake.

In the early days, I learned a lot about the importance of inquisitive history taking. During an on call, I assessed a young man of about the same age as me in A&E. He complained of chest pain and shortness of breath, and it was not difficult to work out that he had had a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in his lung. Under these circumstances, there is an important question about where the blood clot came from and why it formed in the first place. It is a condition that rarely affects fit young men, and this young man was in especially good condition, with well-developed musculature. I was puzzled. Chatting about it over lunch the following day, a registrar from a different team said that it sounded like he had been working out at a gym, and that it was possible that he had been using anabolic steroids. As a musician, I knew quite a lot about recreational drug use, but body building was far outside of my experience. It was immediately obvious that I should have asked him about steroids. Thrombosis and embolism are side effects of anabolic steroids. I frequently asked about anabolic drugs after that, and I was taken aback to realise that many young men of my generation used them.

One morning, it was decided on the ward round that a man in his sixties who had been admitted with pneumonia a week earlier was fit to go home. After the round was over, I returned to his bedside to tell him about his medication and the arrangements for follow up. He took very little notice of what I was trying to tell him. Instead, he thanked me for the care that he had received and kept on asking me about my career prospects and plans. He grabbed my hand in an uncomfortable forced handshake, asking if I was on the level and on the square. Nothing he said made any sense to me at all. I excused myself and caught Nicki in the ward office. I told her that she should come back and have another look at him because we seemed to have failed to notice that he was delirious. The subsequent bedside scene was rather awkward, as the patient had to explain that he had been trying to invite me to become a freemason. Like the use of ‘roids, the arcane rituals of freemasonry had completely passed me by. Good doctors need to understand a lot about lives that are very different to their own. Decontextualised medicine is inadequate. I had a way to go.

Some incidents really drove home the awesome burden of responsibility that was placed on young shoulders. One evening, we admitted a middle-aged businessman who had had a heart attack. The three of us were at his bedside the next morning, doing our post-take round, when his heart stopped. As we were talking to him, he suddenly lost consciousness. He turned deadly pale, then blue, and the ECG monitor at his bedside showed disorganised electrical activity rather than a regular heartbeat. We went into our well-rehearsed routine, and I started pumping his chest. He gasped and opened his eyes with a puzzled look on his face. Thinking that his heart had restarted, I stopped doing cardiac massage. He immediately fell back into unconsciousness. I could not find a pulse in his neck, so I resumed pumping. When he opened his eyes for a second time, he looked straight at me with the most awful look of horror on his face, a haunting and haunted look. It appeared that I had restored his circulation without his heart restarting. It took a long 30 minutes to get his heart beating in a stable normal rhythm. Then we resumed the round without a pause.

What appeared to have happened was impossible according to everything I understood about human physiology. The objective of cardiac massage is to get enough blood to circulate to prevent irreversible tissue damage due to lack of oxygen, especially to the brain. No one believed that it was possible to achieve sufficient blood flow by external cardiac massage to allow the patient to regain consciousness. A few days later, he spoke to me about the resuscitation. “It was awful” he said. “I felt this terrible weight pressing on my chest and it really hurt. I opened my eyes and it was you, but I didn’t know how to stop you hurting me. Then you did stop and I passed out. When I woke up again, I was terrified, because I knew that if you stopped crushing my chest, I would be dead.” I remain uncertain about the physiology of what happened. He recovered and when he left hospital, he gave me a cartoon he had drawn. It showed him in a hospital bed while an announcement is saying “Cardiac arrest, cardiac arrest, Dr Poole to bed 4”. There is an angel on one side of him saying “Keep doing it, Doc, you can save his life” and a devil on the other saying “Don’t bother, go for a cup of tea”. I still have the cartoon somewhere.

House jobs brutalised junior doctors through constant exposure to distress, gore and tragedy against a backdrop of chronic overwork. If you were unlucky, there was also abuse and humiliation from more senior doctors. The experience profoundly changed me and every other house officer. One of the common adverse consequences was the emergence of a degree of indifference to the suffering of others. I think that doctors who are habitually aloof are like that because they cannot cope with emotionally engaging with people who are suffering or dying. All doctors become hard bitten to some degree, because they could not live their lives comfortably if they felt the full weight of the unhappiness that they are exposed to. This probably accounts for the insensitivity and notorious black humour of doctors. I started to become deconditioned when I worked as a psychiatrist, and I revisited a number of events that had occurred during my house jobs with a much greater emotional reaction.

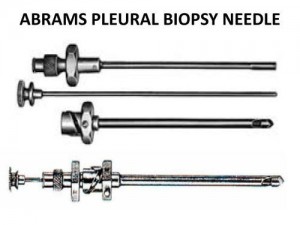

The most brutal part of my job was to drain pleural effusions and to perform pleural biopsies. I always worried about doing physical procedures, because I am notoriously cack-handed. For example, as a student, I had been left to stitch a patient’s finger in A&E. The nurse gave me a heavy duty prolene suture instead of a standard silk one. Prolene is a much stiffer material than silk, but I was oblivious to the difference. When the casualty officer came back to check my work, the sutures unknotted themselves before our eyes. He explained with an air of strained exasperation that you needed to use special knots for prolene sutures, which were in any case completely inappropriate for stitching a split finger. Luckily, the patient was amused. There was a much repeated medical aphorism, “see one, do one, teach one”, which was pretty much how it worked back then. Nicki and Marie were patient teachers who indulged me if I needed to see more than one before going solo.

I was taught the standard method of draining pleural effusions. You pushed a large bore needle into the patient’s chest cavity and drained the fluid with a large syringe. The pleura are membranes that line the chest wall and the lungs, and they are exquisitely sensitive. It was rarely possible to do the procedure without causing the patient significant pain. If too much fluid is drained suddenly, it can damage the organs in the chest. As a massive pleural effusions can contain five litres of fluid, the procedure often had to be repeated daily over a whole week. It made me feel like a medieval torturer. There was usually a need to do a transcutaneous needle biopsy of the pleura as well, which was even more brutal. It was disturbing to repeatedly cause patients pain in such a direct way. It occurred to me that the same result could be achieved by inserting an indwelling catheter with an underwater seal acting as a valve. This equipment was used to drain air from patients’ chests when they had a pneumothorax, which is caused by air getting into the pleural cavity. I could see no reason why it would not work for patients with massive pleural effusions. Dr Fanthorpe told me to give it a go and it worked perfectly. The catheter was clamped and a litre of fluid was drained each day. It was a much less painful process for the patient and I felt better about it. Not surprisingly, other people had the same idea, and the standard modern technique follows similar principles. There is an obvious connection between my aversion to surgery and feeling so troubled by causing patients pain that I invented my own effusion draining technique. Psychiatrists rarely cause their patients physical pain, but the complication is that I have been involved in detaining many people under the Mental Health Act. This is arguably more brutalising than performing a transcutaneous needle biopsy of the pleura, because it lasts a lot longer and has ramifications throughout the person’s life. My only defence against a charge of hypocrisy is that I was never comfortable with either situation. I came to feel that legal powers to detain people with mental illnesses are seriously overused. I never felt that that was true of pleural biopsy.

There is an obvious connection between my aversion to surgery and feeling so troubled by causing patients pain that I invented my own effusion draining technique. Psychiatrists rarely cause their patients physical pain, but the complication is that I have been involved in detaining many people under the Mental Health Act. This is arguably more brutalising than performing a transcutaneous needle biopsy of the pleura, because it lasts a lot longer and has ramifications throughout the person’s life. My only defence against a charge of hypocrisy is that I was never comfortable with either situation. I came to feel that legal powers to detain people with mental illnesses are seriously overused. I never felt that that was true of pleural biopsy.